Our History in Research

British Columbian families’ contributions to NF Research

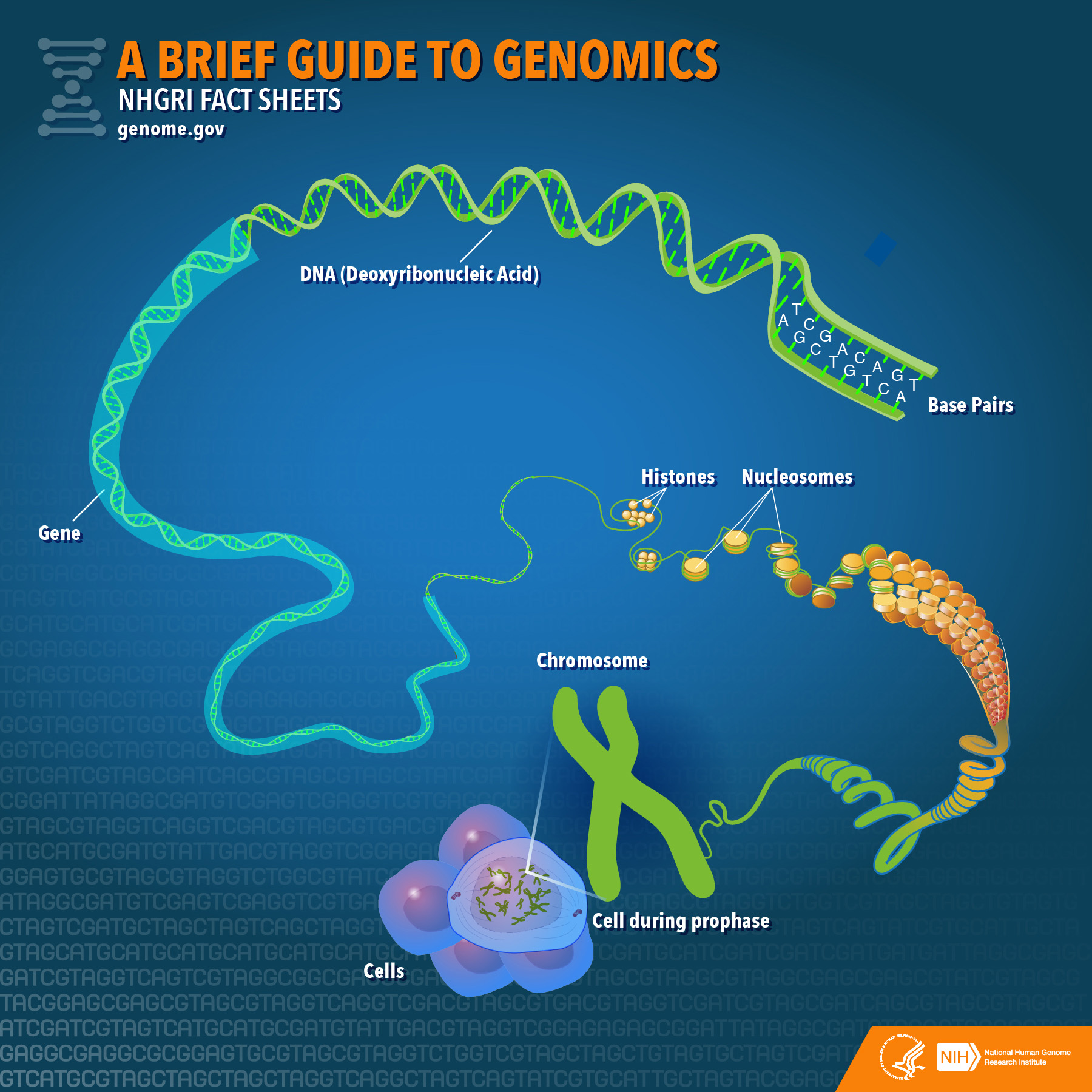

About 28 years ago, the gene that causes NF1 was discovered and later that same year, the Friedman Lab was awarded a contract by the US National Neurofibromatosis Foundation (now Children’s Tumor Foundation) to develop an international database to study the signs and symptoms (the “phenotype”) of all types of neurofibromatosis. Within a few years, we had amassed data from many countries and had begun a research program that centred on analysis of these data. We had a number of wonderfully bright and enthusiastic graduate students to help out. But importantly, at the same time, the British Columbia Neurofibromatosis Foundation (BCNF, now the Tumour Foundation of BC) was blossoming, members were asking questions, demanding answers, and becoming interested in learning about and contributing to research.

At the beginning of 2018, we looked back on the contributions of BC families to the world’s understanding of NF and the many ways the BCNF facilitated this.

In the early 1990s, there were just a handful of researchers studying NF and so it was important for us to work together. BCNF brought key researchers to speak at the annual NF conferences. In doing so, it gave our lab the opportunity to collaborate with some of the best NF minds to try to understand the clinical picture of both NF1 and NF2. Many of the top names in NF: Gareth Evans, Pierre Wolkenstein, Vic Riccardi, Dave Viskochil, Victor Mautner, and others all visited Vancouver to speak to BCNF families and to collaborate with Dr. Jan Friedman and his research team.

These collaborations enabled us to develop a more thorough understanding of NF. For example, our findings enabled us to reassure parents that optic gliomas rarely develop after early childhood, and that certain types of scoliosis or pseudarthrosis are unlikely to develop after the end of elementary school. On the other hand, we discovered that a specific type of congenital heart problem is 10 times more common in people with NF1. These seem like small details but each one helps to put together the jigsaw puzzle of information about NF. We were also able to develop growth charts for NF1 so that people the world over may now use appropriate height, weight, and head circumference charts for their children with NF1.

We worked with data from people with NF2 and developed models of tumour formation that helped to understand the progression of this condition. With Gareth Evans and others, we demonstrated that NF2 tends to be similar in related individuals, which ultimately led to the current understanding of effect of the type of NF2 mutation on disease severity and tumour progression. This is particularly important when people are evaluating the effect of experimental drugs on tumour growth.

BC families with NF listened as we explained new findings at each annual NF symposium. There is always the opportunity for questions and on one occasion at a meeting in Burnaby, some parents asked why their children with NF1 had more dental cavities than those without NF1. We had no idea that this was even an issue, but you told us, in no uncertain terms, that it is a significant problem. Together with BCNF, we designed a study to evaluate this, and many of you may remember receiving dental mirrors in the mail along with a request to count caries and fillings. We published this, and then the whole world knew that dental health was something to be extra careful of, particularly in children with NF1.

The sudden onset of cardio-vascular disease in an otherwise healthy British Columbian man with NF1 prompted our lab to explore vascular disease in NF – a concern that was previously under-appreciated. Many of you came to Vancouver for special testing – including blood work, ECG, and an ultrasound of the artery in the neck. It was quite a commitment. But from these studies, we developed an understanding of the risk of vascular disease in adults with NF1.

The sudden onset of cardio-vascular disease in an otherwise healthy British Columbian man with NF1 prompted our lab to explore vascular disease in NF – a concern that was previously under-appreciated. Many of you came to Vancouver for special testing – including blood work, ECG, and an ultrasound of the artery in the neck. It was quite a commitment. But from these studies, we developed an understanding of the risk of vascular disease in adults with NF1.

Similarly, we became aware of lower vitamin D levels in some people with NF1. BC families contributed to two studies to help us better understand possible links between this and low bone mineral density in children and in older adults with NF1. The results of these two studies help to drive an international project, now underway, to try to prevent bone loss by supplementing people’s diets with vitamin D and calcium. Yes… some of you are involved in that now too.

Much of this detailed work in both NF1 and NF2 was assisted by graduate students or summer students who were often partially funded by grants from BCNF. Many of these students have since taken their expertise in NF1 and NF2 to become researchers and clinicians in areas such as family medicine, otolaryngology, obstetrics, cytogenetics and a variety of other areas.

Much of this detailed work in both NF1 and NF2 was assisted by graduate students or summer students who were often partially funded by grants from BCNF. Many of these students have since taken their expertise in NF1 and NF2 to become researchers and clinicians in areas such as family medicine, otolaryngology, obstetrics, cytogenetics and a variety of other areas.

This page mentions just a few of the studies where BC families or the BCNF/Tumour Foundation of BC, has been central to world-leading research. Of over 60 publications on NF1 and NF2 that have involved our lab, you, or your organization facilitated over two-thirds of them.

Thank you, again.